Introduction

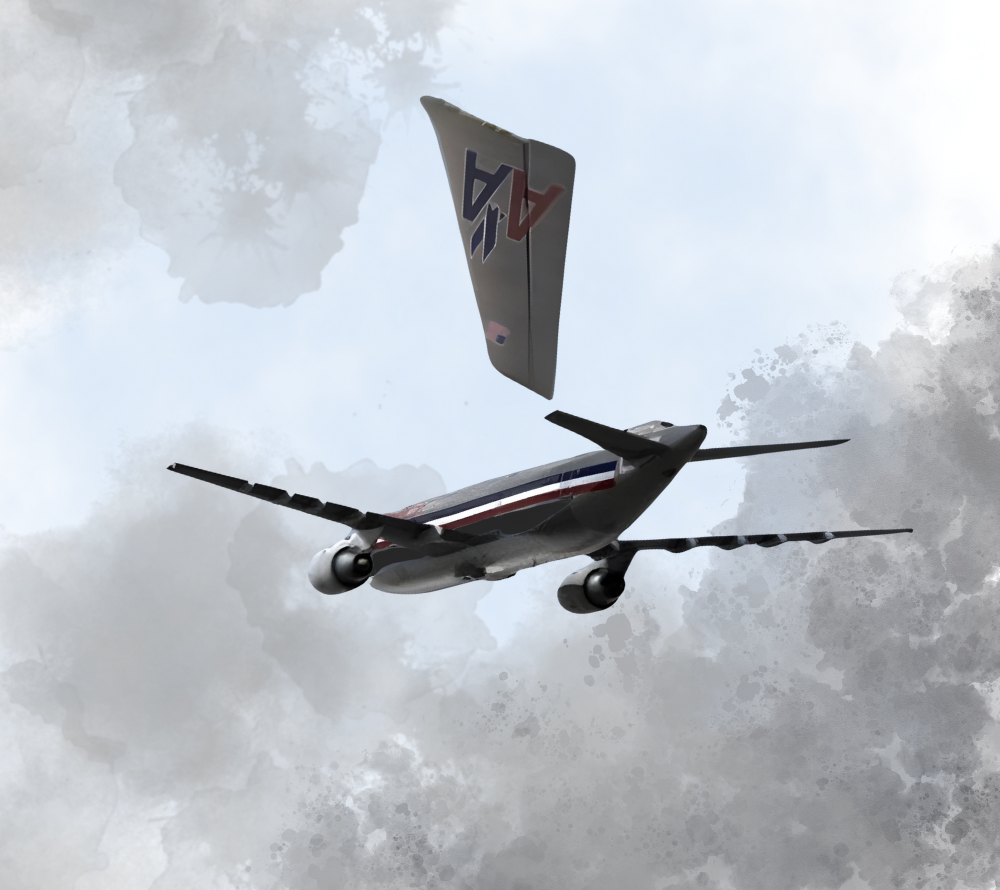

On November 12, 2001, just after takeoff from JFK Airport in New York, American Airlines Flight 587, an Airbus A300-600, crashed into a residential neighborhood in Queens. 265 people died—260 aboard and 5 on the ground—making it one of the deadliest U.S. plane crashes in recent history.

What Went Wrong

1. Excessive Rudder Inputs

Within moments after takeoff, the first officer reacted to mild wake turbulence by making harsh, rapid rudder movements—full left then full right—multiple times. These aggressive inputs created dangerous aerodynamic forces that caused the plane’s vertical tail (stabilizer + rudder) to detach entirely.

2. Sensitive Rudder System Design

The A300-600’s rudder system had light pedal pressure and required only a small movement to create a large rudder effect—especially at high speeds. That made it easy to over-control, even unintentionally.

3. Training That Encouraged Overreaction

The airline's advanced upset-recovery simulator training (American Airlines AAMP) often portrayed turbulence as extremely dangerous—even when it was mild. This exaggerated training likely encouraged the pilot to respond too aggressively with the rudder.

4. Taxiway Confusion

Thanks to the repeated aggressive rudder movements, the forces on the tail reached 203,000 pounds of force—far beyond the aircraft’s design limit of 100,000 pounds. The tail failed structurally, even though it wasn't poorly built.

Consequences

• The Airbus A300 broke apart after its tail separated, killing all 260 people on board and 5 on the ground.

• Large sections of debris fell into a Queens neighborhood, causing fires and building damage.

• The accident highlighted how training and rudder sensitivity could interact dangerously.

• Pilot training for upset recovery was revised, and Airbus issued updates on rudder use.

• Regulators emphasized better simulator training and stricter guidelines on rudder inputs to prevent similar accidents.

The disaster led to major changes in aviation safety:

• Better Pilot Training: Airlines and regulators updated training to reduce aggressive rudder use and to better explain control system behavior at high speeds.

• Design Reviews: The A300 and similar models were assessed for rudder sensitivity and potential design improvements.

• Complex Causes, Not Just Pilot Error: The NTSB emphasized that the crash resulted from multiple factors—design sensitivity, training, and pilot response—not from a single person's error.

Conclusion

The tragic loss of Flight 587 teaches us that even a single pilot’s actions can spiral into disaster when combined with sensitive control systems and flawed training. Aviation has since addressed these lessons. Today, training emphasizes restraint, understanding of control systems, and safer design—and flying remains one of the safest ways to travel.

Modern aircraft and training have improved a lot since Flight 587. Pilots are now taught exactly how and when to use the rudder, with simulators showing the risks of overuse. Airbus and other manufacturers updated their manuals and design guidance, while regulators put stricter rules in place for pilot training. Today, commercial aircraft are safer than ever, and the specific situation that caused this crash is very unlikely to happen again.